stigma: a mark of disgrace

I find it difficult to talk about mental health. It seems much easier to bring up the weather, or the latest annoyances with public transport, or just anything else instead – which is troubling, because it is reported that nearly 50% of the population will experience a mental disorder at some stage in their lives, whether episodic or persistent.1 Half a population is hardly a minority and yet somehow, still there is a fog of stigma surrounding mental illness. Perhaps it is because of the invisibility of the pain – it is difficult to have conversations about the intangible and deeply personal. Perhaps it is fear, or shame, or ignorance. Whatever the reason, it is precisely this silence that contributes to the isolation, the “other-ing”2, and the misrepresentation of those already struggling.

STIGMA: Dismantled, Revealed is an exhibition showcasing creative practices of seven contemporary artists with lived experiences of mental illness and explores their personal relationships with stigma. It is an affecting example of how meaningful discourse could emerge through empowering marginalised voices to be heard and appreciated.

29 cages, Joanne Morgan, 2018.

The complex heaven of a broken mind #1, Cornelia Selover, 2018.

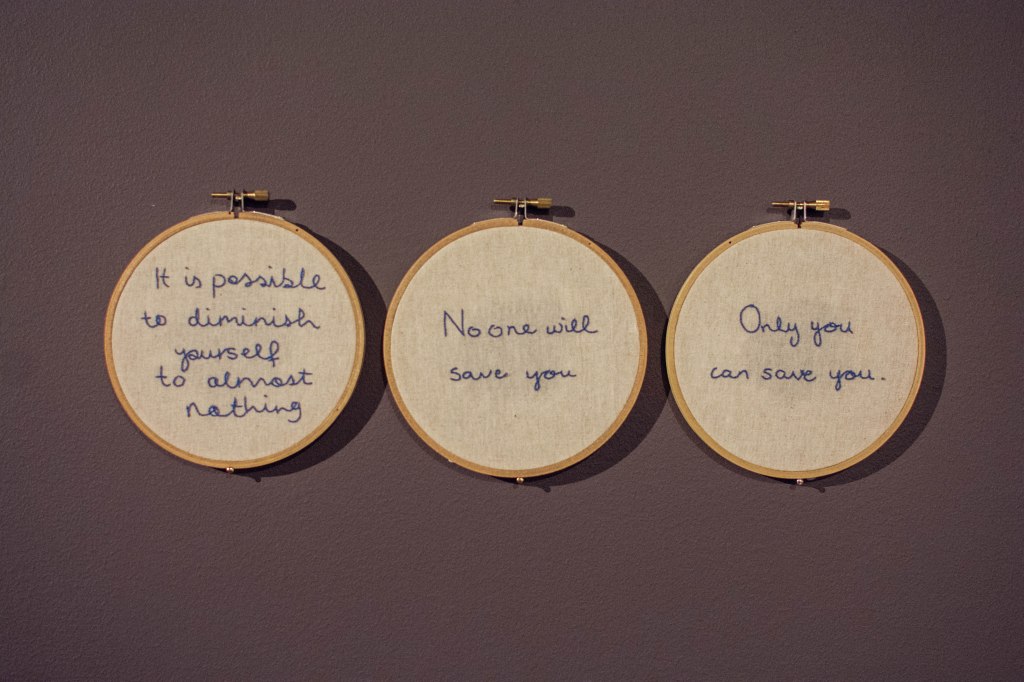

Untitled, Lucy Hotchin, 2018.

dismantle: to take apart

Step into the Melbourne Brain Centre and through the unassuming sliding glass doors of The Dax Centre to be greeted by a varied body work – ranging from watercolours, to embroidery, to sculptural mixed media, to a woven installation. The latter is a piece by current Artist in Residence, Jessie Brooks-Dowsett.

Interlaced, Jessie Brooks-Dowsett, 2019.

From across the gallery, Interlaced appears to be a flexible wire mesh in the shape of an open dome, suspended just above head-height. Visually, it piques curiosity. Hanging down beyond the edges of the structure is an assortment of colourful bits and bobs – translucent tubing, reflective streamers, plastic string, to name a few. They seem incongruous to the overall silhouette, but there is also an unmistakeable carefulness to how they are woven into the wire tapestry. The art of weaving is particularly apt in discussions involving the marginalised – historically it recalls a sense of community 3, of testimonials by those unable to speak under unjust regimes 4, and even of therapeutic healing 5.

However, the form and shape alone of Brook-Dowsett’s work does not fully communicate her considerations about stigma. It is her process in creating it that may be more significant. She had invited gallery visitors to join in her weaving, combining wire and found objects to then later be integrated into the larger installation. There wasn’t a one-sided relationship of art informing viewer. The act of participation and co-creation empowered the artist, who carried her own narratives of stigma, to be the initiator of conversations surrounding mental health.

Brooks-Dowsett in conversation with gallery visitors. Photo uploaded by The Dax Centre’s Facebook page, accessed 10 April, 2019,

https://www.facebook.com/daxcentre/photos/a.262314380605278/1085330608303647/?type=3&theater .

Artist Brooks-Dowsett, herself, explains in the gallery’s Q&A style panel: “there needs to be more conversations about mental health. It isn’t a binary where you’re healthy on one side and sick on the other. There is a continuum.” 6 Her statement underscores her installation and returns in echoes as you explore other works put forth by fellow exhibiting artists; the issue of stigmatisation exists in interwoven narratives. It is a tangle of various systems – from the collective: institutional and medical discourse, media representations, to the individual: internalised self-perceptions, immediate relationships.

“there needs to be more conversations about mental health. It isn’t a binary where you’re healthy on one side and sick on the other. There is a continuum.”

Jessie Brooks-Dowsett

reveal: to make known what was not

I admire how the exhibition does not attempt to be over-ambitious in its disentanglement of stigma. Instead, stays simple and accessible: affirming a misrepresented group, encouraging individual connections within a safe space, and perhaps more importantly, reminding us of the ways we are participants in each other’s experiences.

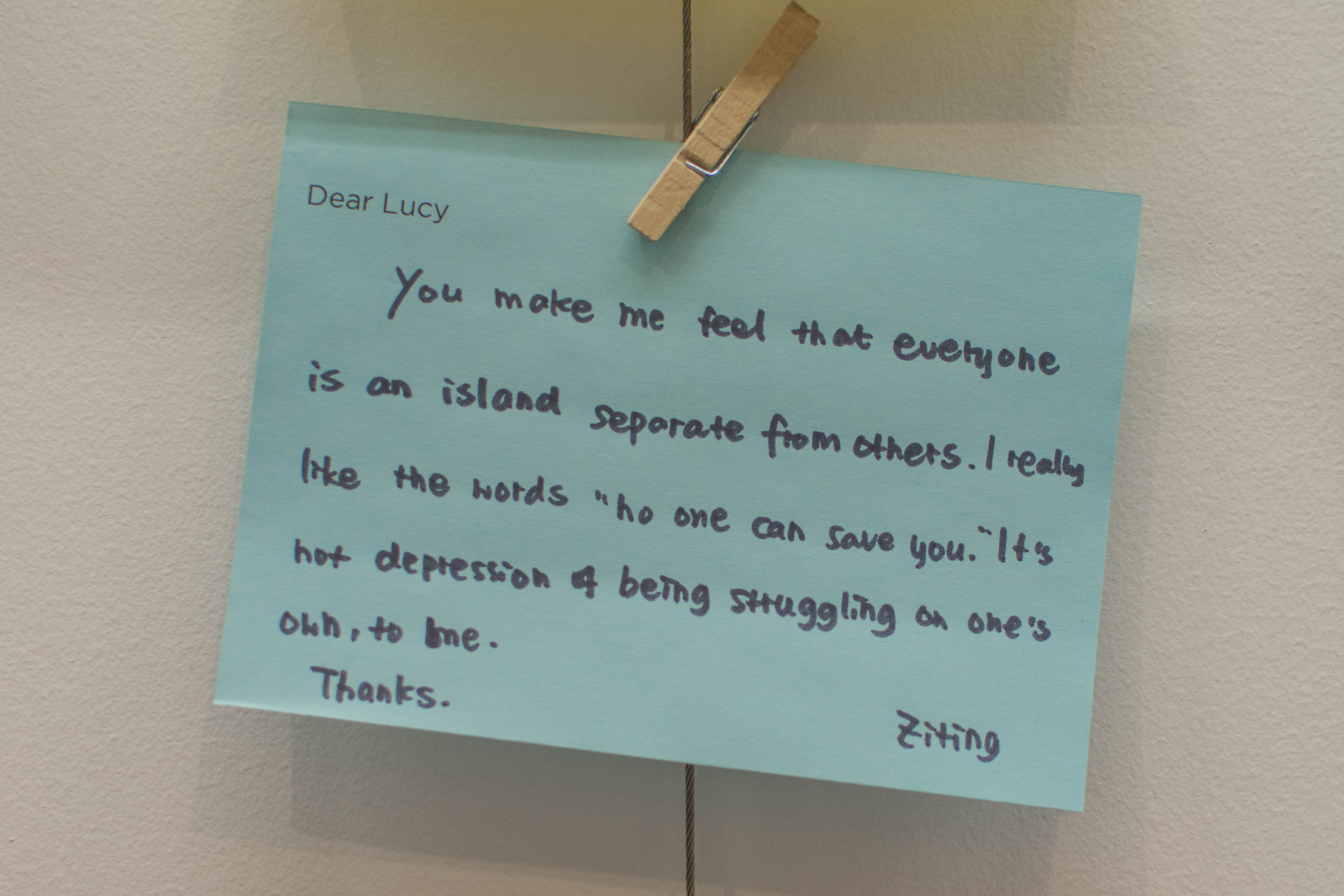

A room for visitors to pen responses for the artists.

STIGMA: dismantled, revealed is currently showing until June 7, 2019. The Dax Centre also runs other public programs such as artist conversations and educational experiences. Do support them and find out more at https://www.daxcentre.org/.

1. Australian Bureau of Statistics, “National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results, 2007”, Australian Bureau of Statistics, accessed April 10 2019, http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4326.0Main+Features32007?OpenDocument

2. Tony Fry, “A Geography of Power: Design History and Marginality,” Design Issues 6,1 (Autumn 1989): 16.

3. Marie Gravalos, “Conceptualizing community identity through ancient textiles: Technology and the uniformity of practice at Hyalcayan, Peru” (Master’s thesis, Purdue University Graduate School, 2014): 138.

4. Here, I refer to quilts made by slaves in which symbols were used to communicate with escaped slaves.

Lisa Garlock, “Stories in the Cloth: Art Therapy and Narrative Textiles,” Journal of the American Art Therapy Association 33, 2 (2016): 60.

5. In art therapy, story cloth can be used when working with trauma survivors.

Ibid, 61.

6. Monique O’Rafferty, “STIGMA: dismantled, revealed artists in conversation,” SANE Australia, accessed April 10, https://www.sane.org/the-sane-blog/wellbeing/stigma-dismantled-revealed-1.

Carla Mosqueda, 27398684

Your introduction points to a really important facet in out society- the invisibility of suffering, the stigma around mental health and the inaccessibility of mental health services for a lot of people has left our society with a lot of blood on it’s hands.

Putting that aside for the moment, the exhibition looks like it is a must-see. I find a lot of beauty in Brooks-Dowett’s work and her processes. I reminds me a lot of how a lot of the time in low periods for myself I will turn to craft as a way to distract myself- sewing, embroidery, oil painting- to have something physical, tangible at the end of a run is empowering in itself.

I can really appreciate how you’ve highlighted the ways in which the exhibition uses more subversive ways to promote discussion around mental health- I often find more widespread metal health themed campaigns to be quite gaudy and unhelpful in their outward approach. Campaigns such as the annual “R U OKAY? Day” festivities that feel like more of a celebration at university campuses, and the “Pause, Call, Be Heard” campaign promoting the lifeline crisis number at railway stations and crossings.

There really is power in giving a voice to those who struggle with difficulties surrounding mental health, and having those voices visible to the public might just be enough to encourage someone else to speak up. In that sense, it appears as though this exhibition might truly have a broader impact than just the art it contains.

LikeLike